Twin-to-twin Transfusion Syndrome 1:

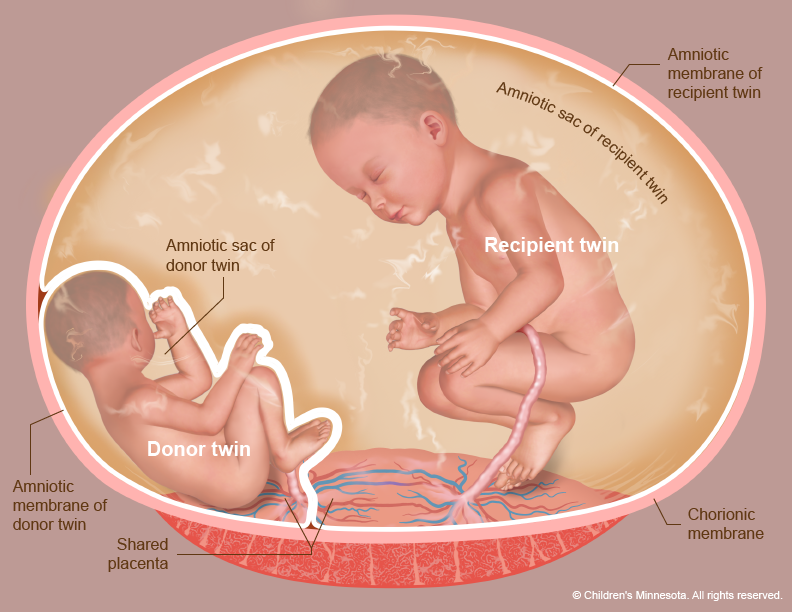

Twin-to-twin transfusion occurs in a monochorionic pregnancy (i.e., identical twins who share a single placenta) when blood from one fetus circulates to the other twin. In general, identical twins normally exchange some blood during gestation; this exchange is usually balanced, so that one twin will act as the ‘blood donor’ one moment, and as the ‘recipient’ the next. The twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome occurs when one twin always ‘donates’ blood to the other, because the communication between the two is unbalanced.

Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome does not occur in non-identical twin fetuses, where each fetus has its own placenta. It is also much less likely to occur if both twins are not only identical, but share a common amniotic space (so-called mono-amniotictwins). The latter is the least common form of twin pregnancies, but is associated with other potentially life-threatening problems.

In the twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, one twin (donor) will have to pump blood, not only for himself, but also to transfuse the recipient twin. The donor has to do more work, thereby having less energy to grow; he will show signs of intrauterine growthretardation, will produce less amniotic fluid (oligohydramnios), and eventually become almost wrapped in its amniotic membranes: there is now so little fluid surrounding him that he is ‘stuck.’ Hence, twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome is sometimes referred to as ‘stuck twin’ syndrome.

The recipient twin, on the other hand, ends up with too much blood and fluids, which forces him to eliminate it through the urine: a recipient twin will therefore often be seen with a full bladder. The excess fluid causes polyhydramnios, the excess accumulation of amniotic fluid in this fetus’s amniotic space. The fetus himself will tend to swell (become edematous), and may go into heart failure, or ‘hydrops’. The combination of polyhydramnios in the recipient and oligohydramnios in the donor is also referred to as ‘poly-oli’ syndrome, another term for twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome

It happens in 5 to 15% of all identical twins

RISK TO THE TWINS

If twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome occurs late in gestation, the risks are usually minimal; if one fetus is threatening to develop hydrops or failure, delivery of the babies might be the best option. If this occurs earlier, before the babies are mature enough to survive out of the womb, the options are fewer and the risks greater .

Preterm, premature rupture of the membranes (PPROM) and premature labor are often a threat to the twin pregnancy, possibly due to increased pressure and increased amounts of amniotic fluid (polyhydramnios in the ‘recipient’ fetus). If the babies are born prematurely, they may be at a higher risk of suffering serious complications, or even dying in infancy.

One or the other twin is at a high risk of suffering severe heart- or brain problems (due to insufficient or inappropriate blood flow caused by the transfusion). The donor twin is usually the sickest; he will often be anemic (not enough red blood cells), and is the one at highest risk of dying in utero.

The recipient twin may suffer as well, and develop hydrops (heart failure) due to fluid and blood overload. In addition, chronic transfusion may make the recipient’s blood thicker (more viscous). This, in combination with somewhat sluggish blood flow because of heart failure, may place the recipient at risk for “vascular accidents” whereby a blood vessel becomes blocked. This may theoretically affect any organ, or an entire limb, causing necrosis. As a result, the organ may be damaged or even absent. Examples of this are an absent kidney, an interruption in the intestinal tract or a severely abnormal leg.

Twin-to-twin Transfusion Syndrome 2:

Once a fetus dies, the remaining twin is at a very high risk of dying within days. If he survives, he is very likely to develop very severe heart or brain damage.

If twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome develops early in pregnancy (before 20 weeks) and nothing is done, there is a very high likelihood that both twins will die.Stages of twin to twin transfusion

stage I, there is severe polyhydramnios around the recipient and severe oligohydramnios around the donor, but the donor is still able to produce enough urine to fill his bladder (which is visible on ultrasound).

In stage II, the degree of transfusion and dehydration of the donor is such, that he is no longer able to fill his bladder – the bladder is now no longer visible on ultrasound.

In stage III, additional signs of fetal stress are seen: there may be pulsatile (rather than uniform) flow through the umbilical vein (usually of the recipient), absent or even reversed end-diastolic flow in the umbilical artery (usually of the donor) or other signs of cardiovascular stress, such as a leaky heart valve (tricuspid regurgitation, or TR). As a group, these signs are called “critical dopplers,” because they are usually diagnosed by using doppler ultrasound (a feature of the ultrasound machine).

In stage IV, there are now overt signs of heart failure in one or both twins: fluid starts to accumulate around the heart (pericardial effusion), around the lungs (pleural effusions), in the abdomen (ascites) or under the skin (edema, or thickened nuchal fold).

TREATMENT OPTIONS

- Observation and bedrest.

If twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome occurs after 25 to 28 weeks, conservative measures (bedrest, single amnioreduction) and early delivery are usually recommended. Amnioreduction means the removal, through a fine needle, of the excess amniotic fluid from the recipient twin with

polyhydramnios (see below). As the pregnancy comes closer to term, it may be best to ‘wait and see,’ and to plan early delivery if either twin shows signs of distress. In this situation, the risks associated with (mild to moderate) prematurity may be smaller than the risk of an intervention in the womb (such as the ones described below).

- Amnioreduction.

Removal of excess amniotic fluid from the recipient twin has been, until recently, the best available treatment for twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome. The reason for its effectiveness is not completely clear, but removing the excess amniotic fluid may help decrease the risk of rupture of the membranes (PPROM) and premature labor. It may also be beneficial by relieving the pressure on the umbilical cord of the twin with excess fluid, and thus improve blood flow between the fetus and the placenta.

Amnioreduction does not, however, treat the cause of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, only one of its effects. Since the fluid is likely to accumulate again (usually within a few days to a week or two), the procedure will have to be repeated. With each amnioreduction, the risk of bleeding or infection increases, as does the risk of injury to the membranes.

The results of repeated amnioreduction depend on how often this has to be done, and how rapidly fluid accumulates again. In general, the earlier in gestation the syndrome develops and the quicker polyhydramnios recurs after amnioreduction, the worse the outcome. Whereas survival of either twin in twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome is very low if the condition develops early (before 20 weeks of gestation), repeated amnioreduction can improve survival of at least one twin to 50-60%.

Twin-to-twin Transfusion Syndrome 3:

Unfortunately, the risks of severe complications in the surviving twins may be as high as 20 to 35%, and includes severe heart or brain anomalies.

3. Laser coagulation of the communicating placental vessels.

This technique, a form of fetal surgery, was originally described in 1995 by Dr. Julian DeLia, and is now being performed in several centers world-wide, including our own. This is the only known form of treatment for twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome where the likely cause of the condition is addressed. In essence, a laser fiber is used, through a very small endoscope (a long telescopic lens) inserted into the uterus, to block all vessels that run from one twin to the other, Fetal surgery is done under epidural or general anesthesia. A small incision is made on the mother’s abdomen and, under ultrasound guidance, a long and thin instrument (less than 1/8 ” in diameter) is introduced into the amniotic cavity. This instrument contains an endoscope, which allows the surgeon to directly look into the uterus; and a laser fiber to coagulate, or block, the blood vessels that are seen to cross from one twin to the other. All other blood vessels, that connect the fetus to its own side of the placenta, are left alone.

Preterm, premature rupture of the membranes (PPROM) usually leads to premature delivery; it is common in twin gestations (5-15%), particularly if TTTS is present. While decreasing the polyhydramnios (see under Amnioreduction) reduces that risk, it may still occur as a result of the invasive procedure itself. After laser coagulation, the incidence of PPROM may be as high as 15%, particularly if multiple procedures (such as repeated amnioreductions) preceded the endoscopic operation.